They sit in a circle, books in hand, ready to discuss the reading they’ve done the night before. Taysia Holbein describes the scene, “They read a few pages and then stop to talk about it.” It’s a book club, right? And that’s exactly what she calls it. But Taysia doesn’t work at a library or a bookstore. The group she describes are children attending the summer program at the Gothenburg Impact Center.

What’s more, this isn’t an assignment. The children in the group voluntarily go home each night to read the pages of the fire fairy book they’ve chosen for the following day’s discussion, and they meet the next day to read and chat . . . about books!

The book group is, in part, made possible by a partnership between Nebraska Children and Families Foundation’s Beyond School Bells (BSB), Nebraska Growing Readers (NGR), Unite for Literacy, and Linked to Literacy. In March of this year, by offering grants of up to $2,500 for literacy projects connected to summer programming, Beyond School Bells implemented what Education Commisioner Brian Maher described as the Department of Education’s vision of fostering “a culture of proficient and lifelong readers in Nebraska.”

Stephanie Vadnais, Assistant Vice President of Community Support and Innovation for BSB, explains that in January, the initiative began working with NGR to build literacy-based projects. BSB would provide funds, and NGR would provide Unite for Literacy books for younger children and expertise in establishing bookstands. Vadnais invited Linked to Literacy to join the effort because they could provide content and resources for older children. The grants were offered at BSB’s yearly Innovation Invitational held at University of Nebraska’s Innovation Campus.

A special literacy grant session at the conference, resulted in 14 awards, some project-based and others community books stands that provide free books to families. Vadnais said it was important to BSB that the projects “focus on the heart of after-school in anything we develop that’s literacy-based.” She explains that she was concerned about funding leading to more school-based focus on drilling in reading basics.

She understands and supports the necessary school-day focus on mechanics, but wants to provide robust, fun, engaging programming for after-school and summer programs that contributes to the love of literacy. She said, “that’s the magic of after-school. If they know they’re learning, they’re having fun. Or, ideally, they don’t even realize they’re learning.” That’s why projects like the book club where kids indulge in the simple joy of reading speak to her.

Holbein, who is a Program Director at the Impact Center, said, “it has been amazing to have these literacy opportunities through the grant because the kids really love it.” The Center has used their funding to create a reading room with comfortable chairs, lamps, and shelves of books the children can take home to keep or bring back for other children to read. Holbein said of the new room, “I wanted to have a space where they (the children) could be calm if they got over-emotional or they had a lot going on.”

Sarah Meyer, who is in her 3rd year as the Childcare Director of Alliance Recreation Center, also used some of her funds to create a dedicated reading area with bean bag chairs and plenty of books. She says that her summer program includes silent reading twice a week and Book Club once a week. Even though she has built in 1-2 hours of dedicated reading each week, she says that her “older kids have actually asked if they can read more.”

When Meyer met with her executive director, they talked about how the past few years had been focused on STEM and so they really wanted “to grow the reading part of our program.” While STEM is still part of the curriculum, they’ve come up with interesting projects like the book box to stimulate interest in reading. The book box project asks children to use a cut out cereal box or a pizza box wrapped in butcher’s paper to recreate a favorite scene from a book. They can draw their scene and decorate the boxes with various materials.

Whether it’s the boxes, the reading area, or just a variety of new books, excitement over reading seems to be growing. Meyer said 2 groups of her older children vied for the books to be used at reading time. She even tells the story of one young boy who stuck his book up his shirt and tried to take it to all of his other sessions. “He is a young man who loves to read,” she says. She added that even in after-school when they would color, he just wanted to read a book.

One of the most interesting projects to come out of the grant funding came from Wakefield. Cathy Hoffart, a 1st-grade teacher there for the last 28 years, fell into the grant funding because her close friend was headed to the Innovation Invitational and asked Hoffart to join her.

Wakefield schools offer the large migrant population of the community a month of summer enrichment where K-5 students engage in literature, math, science, and social studies activities while going on field trips as well. Hoffart saw an opportunity to use grant funding for a photography project that would not only involve children in reading but also teach them useful skills in image creation and in book production.

Because they loved the Unite for Literacy books and the fact they are translated into so many languages, they decided to follow the Unite for Literacy model of the books provided by NGR. Hoffart challenged each age group to make a book based on the A-C levels Unite has established. The youngest used very simple and short sentences with photos; the older B-group would write 2 or 3 sentences to accompany their photos; and the oldest C-group crafted more complex text to go with their pictures. Students learned basic photographic skills, such as the “rule of thirds,” using the horizon, and composition, and, Hoffart said, “they did all the photography. We went all over town and they took photos.”

The project was called “Around the World and Right Back Here at Home.” Children learned about different countries, studied maps, and even received pretend passports they could stamp with the various countries they had learned about. But, as Hoffart put it, “when it comes down to it, our communities are where we feel most at home.” That’s where the photo books came in. Students were asked to embrace their own community and to capture it in the photos they took.

“The kids went crazy and and absolutely loved it!” Hoffart said. One of the best outcomes came from a group of 4th-, 5th-, and 6th-grade boys for whom, Hoffart said, “summer school wasn’t so cool.” On the first day, when she announced the photography project, their reaction was negative, but they actually got to bring their smartphones to school and to use them, which, Hoffart points out, doesn’t happen very often. Wakefield is the baseball capital of Nebraska, and the boys decided to document the Wakefield baseball complex. Hoffart said, “those were some of the best pictures we got—the ones from those boys.” She added, “when those big boys caught on, that was so meaningful.”

Kim Harder had a similar impulse to engage her most reluctant readers. Harder has worked in Beatrice schools for 8 years and is Coordinator of the Beatrice Learning After-School Time (BLAST) program. She, too, heard about the BSB grants at the March conference and used funding she received for her “Best Possible Summer” curriculum.

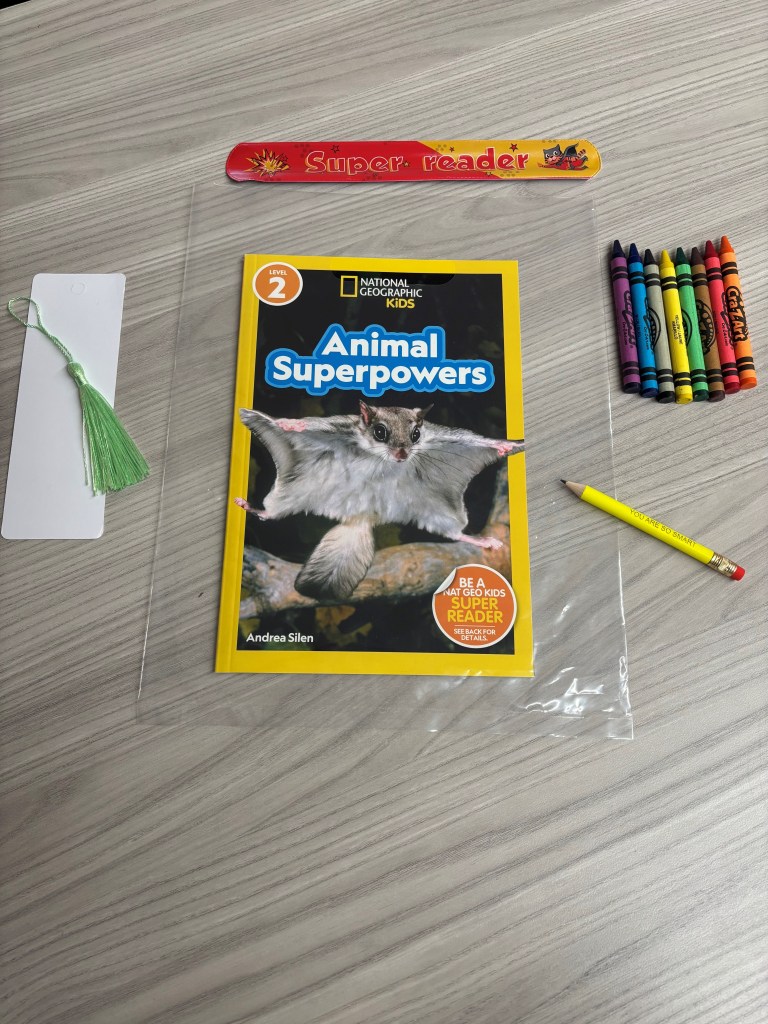

She used her literacy funding to provide students with bags that contained books they had chosen, all materials necessary to make a bookmark, crayons, pencils, a reading log, and tips for families on helping younger children with reading. Because she knew there were some 4th– and 5th-grade boys who weren’t interested in reading, she involved them in the project by asking the kinds of books they would like to read. She found some good sports books and graphic novels based on their lists and made sure to make them available. Harder said, “that was probably my favorite thing, actually seeing those kids who don’t really read during the school year actually read.”

While these programs have done excellent work in encouraging reading in the children they serve, Vadnais underscores an important consideration, “they’re (the children) with their families many more hours than they’re with these programs. We want to contribute to a family culture of reading.” A requirement then of the grants was to incorporate a family engagement element for each project. Hoffart, for example, went to Shutterfly and had hard bound copies of her students’ photography projects made. The children then had a family day where they were able to present those books. Meyer will hold a Back-to School night with families where her students will present their book boxes to their families, and Harder invited families in for cookies and to chat about her program.

The outreach to families has paid off as many of the participants have stories to tell of the literacy efforts extending beyond the actual program. Harder said that when older children were encouraged to take a book home for their younger siblings, even some of the younger kids asked to take one to an older sibling. In addition, she said that some families asked to grab books for their other grandchildren not involved in the program. Holbein also said that older students were taking books home to their younger siblings.

Vadnais sees these projects as an opportunity to connect families to literacy resources and emphasizes that “it really does matter how families are approaching books and reading at home. That has a lot more impact on kids.” Because BSB wants to see the impacts of the programs, they are tracking time spent reading and are conducting family surveys. Each project is also asked to write a narrative report on their work.

Vadnais hopes the outcomes they gather will lead to continued and future funding. This year’s efforts resulted in 11 bookstands and 3 projects, but she would love for BSB to offer additional mini-grants in the future. To establish the continuity and longevity of the programs, communities and school districts need to invest in literacy efforts and partner to extend efforts in the future. Schools will continue to establish the foundational skills of literacy, but communities, families, and after-school partners have the opportunity to remind students that reading is fun. They too are an integral part of the process and can, as Vadnais puts it, “build back a love of reading.”

© 2025 Nebraska Children and Families Foundation. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment